by Francesco Domenico Attisano, Fabio Accardi & Roberto Rosato

A quick overview on historical trend of global risks, as outlined by the Global Risk Report, with a focus on the last two years in particular, and of the outlook drawn in the latest GRR edition, can help us to take out relevant insights on risk governance and compliance.

The change in the perception of global risks: historical trend 2007-2020

As per GRR 2020, considering a time frame up to 20141, the most perceived risks in the international community were those having economical and financial nature.

In the following years, the risks perception has changed, with a prevalence of other risk categories such as environmental, geopolitical, social and technological.

From 2016 to the present day, geopolitical risks (weapons of mass destruction) and environmental have ranked as top risks with the greatest impact. In terms of likelihood, the growing importance of technological risks (connected to the digital revolution and IT security) should be highlighted.

Pandemic emergency and environmental risks: GRR 2021 focus

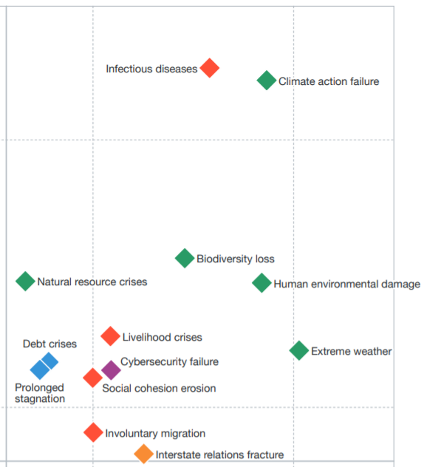

Let’s focus on what is reported in the GRR 2021 (see figure 1). In the graph, risks are classified in terms of impact and likelihood: therefore, on the right-hand side at the top are placed the greatest risks at a global level. As it is reasonable to assume, the pandemic emergency makes social risks regarding infectious diseases the paramount. In a similar position we find environmental risks related to the failure of actions aimed at mitigating climate emergency risks. Other environmental risks (such as losses related to biodiversity and deterioration of the habitat) are immediately below. The quadrant is completed with social (crisis due to lack of livelihoods), technological (Cybersecurity failures) and economic (debt crisis and prolonged stagnation) risks.

Figure 1: Processing and translation of data taken from Global Risk Report 2021 (Global Risks Landscape), taken from Fabio Accardi Op. Cit.

GRR 2022: The evolution of the global risks perception in the short, medium and long term

The latest report depicts the results of the latest Global Risks Perception Survey (GRPS), followed by an analysis of the main risks emerging from current economic, social, environmental and technological tensions. The report closes with deliberations on strengthening resilience, drawing on the lessons of the last two years in check from COVID-19. There are always strong concerns from the global community about social and environmental risks. When asked to evaluate the last two years, GRPS respondents perceive social risks, in the form of “social cohesion erosion”, “livelihood crisis” and “deterioration in mental health”, as those whose severity it has increased the most since the start of the pandemic2.

Over a 10-year prospect, the health of the planet dominates concerns: environmental risks are perceived as the five most critical long-term threats to the world and also the most potentially harmful to people and the planet, with “actions for climate change failures”, “extreme natural events” and “biodiversity loss” which rank among the top three most serious risks.

Respondents also reported “debt crisis” and “geo-economic conflicts” as among the most serious risks over the next 10 years. Technological risks (such as “digital inequality” and “cybersecurity failure”) are other critical short- and medium-term threats to the world according to GRPS respondents. However, these categories do not appear among those most perceived in the long term; GRR 2022 itself marks this issue as critical, classifying it as a possible blind spot in risk perception.

Lessons to learn from the past and food for thought to increase our resilience capacity

Reading the GRR makes us understand the significant interconnections between the main risks, when considered globally. Examples are the links between external environment degradation, lack of livelihoods, habitat degradation and the spread of infectious diseases. The pandemic emergency has also resulted in the acceleration of digitalisation processes, creating opportunities for change but also disparities and inequalities and increasing exposure to cyber security risks (cybersecurity). In this sense, it would be critical if we should underestimate the potential severity of these risks in a long-term perspective.

These considerations make it clear how important it is to think timely about the mitigations that can be adopted, learning from the lessons that past events have made us understand. Our ability to adapt in positive terms to changes, or resilience, is a condition of survival in complex scenarios and consequent challenges that the internal and external environment poses for us.

This should make us reflect: in the preface of the 2021 report it was highlighted that since 2006 the risks of pandemics were well known and reported. In subsequent years, avian flu (2009 and 2010) and Ebola (2016) led to the reporting in subsequent report editions with recommendations aimed at greater global collaboration to prevent and mitigate catastrophic effects. These flash-forwards have not prevented Covid-19 from determining the consequences that we all know in 2020.

A reasoning is, therefore, necessary on how the different actors can cooperate in an integrated way to mitigate and monitor risks. In fact, it has been understood that the solutions arise from a greater awareness and perception of the negative events that may occur in future scenarios.

A prerequisite for this awareness is the increase in “risk culture”[2], both at the individual and economic, social and political levels. Future challenges cannot be faced without an integrated and global governance approach.

How can we gear up to increase organisations’ resilience in facing global risks that are now intensified by the pandemic emergency? In general terms, the GRR suggests four areas of possible improvement in global risk governance, as summarised below:

1) Frameworks

These are detailed analytical framework that provide a holistic and systemic view of the impacts of risk and help to bring out potential vulnerabilities and negative repercussions. The integrated approach requires an active role of multilateral institutions and continuous collaboration between public authorities, private companies and civil society to facilitate systemic perspectives.

2) Risk Champions

There is the need to invest in high-profile “risk champions” who can coordinate different players to stimulate innovation in risk analysis and response capabilities, and to improve relationships between subjects expert matters and political leaders. There is the need as well to promote the establishment of institutional subjects (“National Risk Officers”) with the mandate to improve resilience and increase the organisational and decision-making culture.

3) Communication

It is utmost important improving clarity and consistency in the management of risk communication and in fighting against disinformation. Crises require responses from all players involved: confusion and lack of clarity can undermine efforts to build trust and resilience among the public sector, private sector, community and families.

4) Public-private Partnerships

The pandemic has shown how innovation can be triggered when governments are able to engage the private sector to respond to major challenges. A prerequisite for this is that risks and benefits are shared equally and appropriate governance is in place.

These areas for improvement converge towards an integrated approach and global cooperation aimed not only at managing the consequences of crises, but at anticipating and detecting potential new crises as they arise. In this sense, the GRR highlights how the best results have been obtained where the nationalistic pressures to manage the effects of the pandemic disjointedly have been balanced by integrated risk responses, starting from the sharing of data base on research results in the vaccines’ effectiveness until the management of machinery to ensure the conservation of vaccines and their inoculation.

A scheme for analysing the integrated strategic approach to risk and control governance management

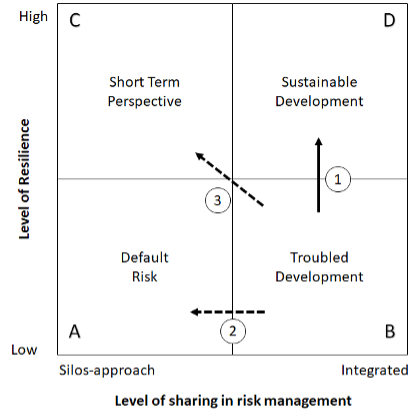

The matrix below seeks to pool the reflections on the importance of an integrated strategic approach to risk management and controls, showing the possible relationship of resilience capacity and existence of an integrated and shared approach to risk management.

The four quadrants of the matrix reveal areas that we will connote, trying to identify possible organisational models of reference.

Figure 2: Risks of resilience and sustainable development, from Fabio Accardi Op. Cit.

The lower left quadrant encompasses organisations that tend to suffer, with poor resilience, the consequences of scenario changes, without having carried out any mitigation action. The corresponding organisational attitude is to believe that any solutions, even “ex post” to unexpected events that generate emergency situations, should be identified within the internal subsystems and not with cooperation and collaboration with other players and external parties. In this area Governance Systems can be classified as “autarchy oriented”, and we can describe them as “at risk of default”. On the contrary, in upper right quadrant we will place the organisations that can effectively pursue “sustainable development” goals. In this quadrant there are organisations that take advantage of the opportunities for external change to improve their competitive positioning by investing in innovation. These organisations are also aware of the fact that emerging risks require an integrated response and, therefore, will adhere to all collaboration and cooperation initiatives also with external authorities, institutions, parties aimed at sharing data and solutions and not just competition. Operating in a logic of sustainability involves abandoning the “backyard” approach.

The upper left quadrant includes situations in which the awareness that risks must be governed takes over and this increases the capacity of resilience and, therefore, of resistance and reaction. However, the fact that the responses that are identified, are not integrated and shared with other external players, limits the effectiveness of the strategies implemented: this places these behaviours in a perspective of “short-term survival” objectives. The reason is that some risk categories, such as cyber risks, cannot be mitigated without an integrated responses that involve the combined effort of different players. Failure to perceive this makes systems vulnerable and with limited defense capabilities.

The lower right area, where a low level of resilience is associated with a high level of predisposition to manage risks in an integrated and shared way, is certainly the most complex: we can define it as “problematic development”, in a simplistic way. The effort towards integrated and shared solutions, that does not raise the level of organisation resilience, is a symptom of deficiencies in the risk management system, deriving form weaknesses in the control systems. The identified risk responses could be correct, but the controls set up are inadequate. The possibility of increasing the resilience maturity is therefore subject to the fact that mitigating actions are implemented, in order to resolve deficiencies and restore system to a virtuous condition, possibly starting from the previous stage (default risk, director 1). Otherwise, in the absence of corrective actions plans, the condition could evolve towards a state of uncertainty and default risk and fall towards other matrix quadrants, other than sustainable development (dotted directors 2 and 3).

Conclusions

To conclude, we believe that the right approach starts from an attitude aimed at anticipating the consequences of negative events rather than suffering them, providing adequate support for implementing the best strategies aimed at organisational resilience. Risk Control Governance must be considered in an integrated view and must be continuously updated, in order to be resilient.

Note

Figure 1 and 2 and related comments are an abstract of the concepts presented by Fabio Accardi in his last book (2021) “Governo e controllo dei rischi – Manuale per scelte consapevoli e sostenibili. Metodologia, casi ed esemplificazioni”; Franco Angeli Edition

Article written by:

Francesco Domenico Attisano CIA, CRMA, CCA, QAR, is a Lead Auditor ISO 37001. He is also a Knowledge & Technical Manager at the Institute of Internal Auditors, Italian Chapter and Partner at operàri S.r.l. BCORP. He is a Strategic Consultant in Internal Audit, Risk & Performance Mgt, Anti-corruption & Compliance. He is also an author at the Italian website www.riskcompliance.it

Fabio Accardi is a Contract Professor of Business Auditing and CEIS Fellow at the Tor Vergata University in Rome. He is a faculty member of executive programs and courses at AIIA and Luiss Business School, and President of various Supervisory Bodies ex Dlg.s 231/01.

Roberto Rosato is an Internal Audit Manager at Webuild, CIA, CCSA, and has a Master of Science in Economics and Business. As of 2021, he is the Head of Internal Audit of Lane, the US Webuild strategic subsidiary. Previously, he worked as Astaldi’s Internal Audit Manager, focusing on operational audit, and as a consultant for PwC and Ernst & Young, business risk services. He is a member of the AIIA Publishing and Publications Committee, author of publications on Internal Control and Risk Management, and a AIIA teacher.

[1] The two-year period 2012-13, indeed, was still affected by the crisis started in the USA in 2007, relating to securities linked to mortgages granted to debtors at risk of insolvency (subprime). The crisis spread globally, forcing support actions by governments and institutions in favor of banks and businesses. Hence financial crises and failures were considered global risks with greater impact. [2] Only 16% of respondents feel positive and optimistic about the outlook for the world and only 11% believe the global recovery will accelerate. [3] Cfr. F.D. Attisano (2020), “Tone from the top e risk awareness funfamental drivers of risk culture”; www.riskcompliance.it