Philip R. Lane, Member of the Executive Board of the European Central Bank, recently gave a speech at Bruegel, Brussels, on 5 May 2022. There are three main analytical challenges in assessing the economic and inflation outlook for the euro area. First, the pandemic remains a first-order driving force. Over the winter, pandemic restrictions still limited economic activity in the euro area. While these restrictions are currently being lifted and case numbers are declining, the current set of restrictions in China is contributing to a further wave of bottleneck pressures in global supply chains and limiting domestic demand in a major region of the world economy. At the same time, the re-opening of the European economy and the prospects for a more normal summer tourist season are set to provide significant momentum in the coming months, especially for services sectors and tourist-intensive countries.

Second, the significant jump in energy prices since the summer of 2021 represents a major macroeconomic shock. In particular, since oil and gas are primarily imported into the euro area, this constitutes a major adverse terms of trade shock, reducing the aggregate real income of the euro area. In addition to the adverse implications of lower real income for consumption and investment, a persistent increase in energy prices may reduce aggregate supply capacity by making it uneconomic to operate energy-intensive production technologies at full capacity in some industries. This concern applies especially to the tradables sector to the extent that there has also been an increase in the relative price of energy in Europe compared to other parts of the world. In terms of inflation dynamics, even if a rise in energy prices is ultimately a level effect, a protracted phase of temporarily-high inflation runs the risk of affecting medium-term inflation dynamics through a re-setting of inflation expectations.

Third, the Russian invasion of Ukraine is a watershed for Europe. The economic impact of the war is operating through several mechanisms including: the amplification of the energy shock; a new set of bottlenecks; and downward revisions in consumer and business confidence. Moreover, the war constitutes a significant source of uncertainty, which is acting as a further drag on economic activity.

In what follows, I review some of the implications of these three forces for the economic outlook and the inflation outlook. I do not attempt to provide a comprehensive overview: rather, the aim is to highlight some of the factors relevant for understanding the current situation.

Economic developments

High energy costs, pandemic-related restrictions, global bottlenecks and, latterly, the initial impact of the war go some way towards explaining the subdued economic performance of the euro area in the last quarter of 2021 and the first quarter of 2022: the quarter-on-quarter growth rates were just 0.3 per cent and 0.2 per cent respectively. Although the easing of pandemic-related restrictions in Europe will provide an important source of momentum in the coming months (especially for the services sector), the pandemic is still contributing to global bottlenecks, while the energy shock and the war will continue to exert an adverse impact on domestic activity.

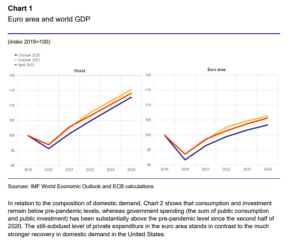

Chart 1 shows different vintages of the IMF’s World Economic Outlook. Compared to the profile of a prolonged multi-year phase of output remaining far below the pre-pandemic level that was embedded in the October 2020 vintage, the development and rollout of vaccines (together with considerable policy support) enabled a much faster recovery, as captured in the October 2021 vintage. However, the impact of new pandemic waves, the energy shock and the war have all contributed to a substantial downward revision in the expected output path, as reflected in the latest April 2022 projections. During 2021, the faster-than-expected global recovery – in combination with the asymmetric and idiosyncratic nature of the impact of the pandemic across industries and regions – helps to explain the emergence of sectoral demand-supply mismatches (bottlenecks) and the jump in energy prices.

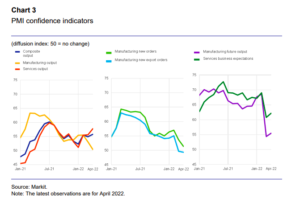

Chart 3 shows a range of Purchasing Managers’ Index (PMI) confidence indicators. The left panel shows the assessment of the current situation in manufacturing and services. The re-opening of the economy is supporting the continuing improvement in the services sector. Although the manufacturing indicator edged down in March, it remained broadly stable in April, so that the overall profile has so far been resilient to the outbreak of the war. However, in the middle panel, we see that this resilience did not hold for export orders, which have declined more than total orders, since the war and the Covid wave in China are already affecting the external sector. The right panel shows the expectations component, which fell abruptly for manufacturing in particular but has remained in expansionary territory. This can be interpreted as an expectation of a slowdown in growth but not a recession.

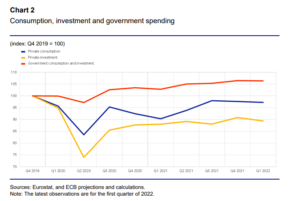

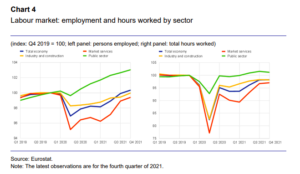

Turning to the labour market, Chart 4 reinforces the message of Chart 2: the recovery in the labour market has been asymmetric, with public sector employment above the pre-pandemic level, employment in industry and construction only now reaching the pre-pandemic level and employment in services still below the pre-pandemic level. As indicated in the right panel of Chart 4, the distance to the pre-pandemic level is larger for the intensive margin (hours worked per employee) than for the extensive margin (numbers employed). At an aggregate level, the ongoing reduction in the unemployment rate and the recovery in the labour force participation rate underline the overall improvement in the labour market.

At the same time, the downward revision in the expected output path as a result of the war and high energy prices will have implications for the future evolution of the labour market. In terms of the impact of the war on the labour market, Adrjan and Lydon (2022) highlight a striking pattern in online job postings: since late February, the growth rate of job postings — in the twenty-one European countries with an Indeed job site — has on average fallen eight percentage points relative to their immediate pre-war trend. Of course, this aggregate shift should be interpreted in the context of the significant positive trend in recent months and take into account the different dynamics across countries.

Inflation

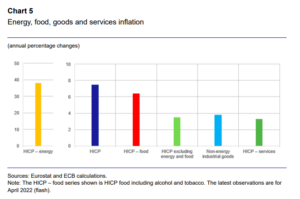

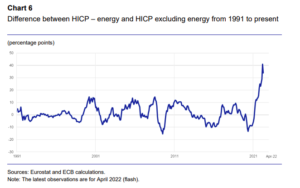

Chart 5 shows the change in the price level over the year from April 2021 to April 2022. Energy prices have increased by about 40 per cent. This increase in the relative price of energy is far higher than the individual spikes experienced in the 1970s. It is also four times larger than the energy price spikes previously observed over the last two decades since the creation of the euro (Chart 6). Chart 5 shows as well that the other main categories also have seen above-target inflation rates over the last year, especially the food category.

In understanding the factors driving price increases across sectors, it is important to bear in mind that the rise in energy prices puts upward pressure on costs across all sectors, given the importance of energy as a production input in the food, manufacturing, construction and services sectors. [ ] Bottlenecks are also generating temporary upward pressure on costs, even if the eventual resolution of these bottlenecks should reverse these cost pressures in the future. In addition, the lifting of Chart 5 Energy, food, goods and services inflation (annual percentage changes) Sources: Eurostat and ECB calculations.

Note: The HICP – food series shown is HICP food including alcohol and tobacco. The latest observations are for April 2022 (flash). Chart 6 Difference between HICP – energy and HICP excluding energy from 1991 to present (percentage points) Sources: Eurostat and ECB calculations. Note: The latest observations are for April 2022 (flash). 3 pandemic restrictions can be expected to generate temporary price pressures in re-opening sectors, in view of the recovery in demand for newly-unrestricted services and initial supply and labour market constraints in these sectors.

To view Philip R. Lane’s full speech, click here.