by Margrethe Vestager

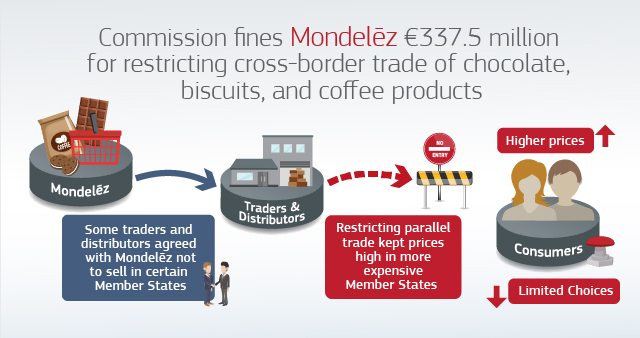

The Commission has fined Mondelēz 337.5 million euros. We have done so because they have ben restricting the cross-border trade of chocolate, biscuits and coffee products in the European Union. We find that Mondelēz illegally restricted retailers from sourcing these products from Member States where prices are lower. This allowed Mondelēz to maintain higher prices. This harmed consumers, who ended up paying more for chocolate, biscuits and coffee. Mondelēz is one of the world’s largest producers of very well-known brands that many of us would buy on a daily basis. Just to name a few, Milka, Toblerone, Côte d’Or, Cadbury, Tuc, Lu, Ritz and Oreo are all Mondelēz brands. So this case is about the price of groceries. It is a key concern to European citizens, even more obvious in times of high inflation where many are living in cost-living crisis. It is also about the heart of the European project: the free movement of goods in the Single Market.

In the Single Market, traders can buy products in Member States where prices are lower and they sell them in Member States where prices are higher. By doing that, putting a pressure for prices to come down. This is called ‘parallel trade’. It increases competition, lowers prices and increases consumer choice. EU citizens should benefit in this respect from the Single Market. They should be able to buy cheaper products when they can be sourced at a cheaper price from another Member State. They should be free to do so in supermarkets, when retailers import the cheaper product. And any company that hinders this freedom engages in illegal behavior and should be sanctioned accordingly. We started looking at this case back in 2019. We carried out inspections at the premises of Mondelēz.

Two different types of infringements

First, Mondelēz entered into anticompetitive agreements to restrict the cross-border trade of its products. This is a breach of Article 101 of the Treaty. Second, Mondelēz abused its dominance for chocolate tablets in certain national markets also to restrict imports. This is a breach of Article 102 of the Treaty. Looking at the first infringement type. We find no less than 22 separate breaches of Article 101. These agreements pursued two main goals:

*First Mondelēz entered into agreements with certain traders to determine the territories where they could sell Mondelēz’ products.Why would it do that? Because, by restricting parallel trade, Mondelēz isolated national markets within the European Union from outside competition. In this specific case, Mondelēz was selling a range of products at different prices in different Member States. It wanted to control where and to whom its products were resold by the traders. In Member States where it charged higher prices, Mondelez ensured that prices remained high. To achieve this, Mondelēz agreed with traders on the territories where they would sell or not sell. There were eleven separate agreements concerning seven traders.

*Second, Mondelēz blocked some exclusive distributors in certain Member States from selling Mondelēz’ products to customers located in other Member States. These distributors enjoyed an exclusivity to sell certain products in a given territory. But traders or retailers from other Member States are normally free to buy products from them. But Mondelēz prevented distributors from making such sales. Either by imposing contractual restrictions or by asking them to request permission on a case-by-case basis. Mondelez restricted eleven distributors in this way.

These are very serious restrictions of competition. They fragment the Single Market. They isolate national markets within it. And they prevent the free movement of goods across the European Union. This conduct harms consumers and deprives them from the benefits of the Single Market. Moving now to the second infringement type: the abuse of dominance, which is a breach of Article 102 of the Treaty. We find two such abuses. In one instance, Mondelēz took Côte d’Or tablets off the market in the Netherlands. It did so to prevent retailers from reselling them in Belgium, where Mondelēz sold many more Côte d’Or tablets at higher prices. In another case, Mondelēz prevented a wholesaler from buying its chocolates in Germany, where they were cheaper, and resell them elsewhere in the European Union. Mondelēz refused to supply this wholesaler for four years. By doing so, Mondelēz prevented this wholesaler from putting pressure to lower its prices in several Member States. Such abuses artificially partitioned the Single Market, and that has a negative impact on price and consumer choice in the EU.

Now, I also want to recognize Mondelēz’ cooperation in the investigation. We have a cooperation procedure in our toolbox, which requires companies to acknowledge the infringement and to cooperate. In exchange, companies obtain a reduction of the fine that they are to pay. This procedure leads to considerable advantages in terms of speed and efficient resolution of cases. So the Commission has decided to reduce Mondelēz’ fine by 15% in light of its cooperation.

The level of the fine

The infringements covered a large part of the European Union. They lasted between 2006 and 2020, except for coffee products which Mondelēz divested back in 2015. We set the fine in view of the factors that we usually use. We considered the value of Mondelēz’ sales of the products concerned, the gravity of the infringement, the duration of the infringement and Mondelēz’ cooperation. Finally, we also took account of the fact that this type of behaviour has already been sanctioned in the past. This is really not a novel case. We have a clear case practice. We have a track-record of fighting territorial restrictions. The fact that they are illegal and violate competition rules is well established and companies need to bedeterred from engaging in this type of illegal conduct.

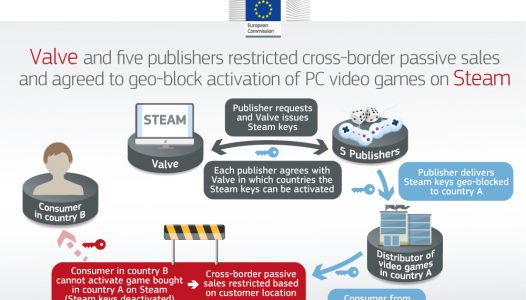

Based on these elements, we decided to impose a fine of 337.5 million euros. The decision is another example of our efforts to deter companies from engaging in illegal behaviour that fragments the Single Market. We have taken decisions against the beer brewer AB InBev in 2019 and against Valve and video games makers in 2021. We are determined to uphold the fundamental freedoms in the EU and to ensure that EU citizens have access to the biggest variety at the lowest prices that the market can offer.

The cost and quality of food is a core priority for European citizens. This case is also part of a broader effort to enforce competition rules in the food retail industry. This is a sector in which we have several ongoing investigations, such as the ones in food delivery services and in energy drinks. Our sustained enforcement of competition rules in this sector is an important part of the effort to ensure that consumers have access to lower prices, especially in times of high inflation.

Margrethe Vestager is Executive Vice-President of the European Commission and Commissioner for Competition.