by Klaas Knot

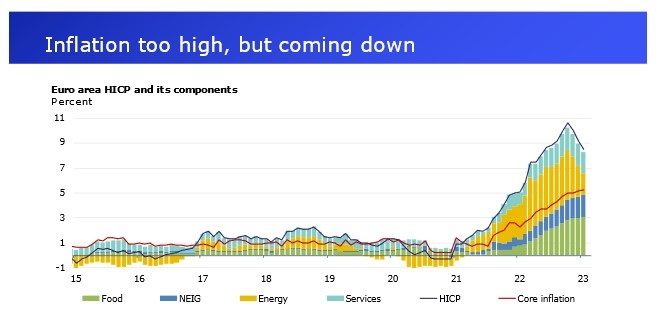

I will attempt to walk you through the evolution of our inflation problem and the implications this carries for ECB policy in the next few months. As you all know by now, the decade of below-target inflation swiftly came to an end in the course of 2021. Our economies rebounded from the pandemic with households disbursing their growing deposit balances, but also with supply still severely constrained after a long period of pandemic contagion measures. Headline inflation approached an unprecedented 5% already in 2021. The unconscionable war in Ukraine, and the associated pressures in energy and food supply then pushed headline inflation into unprecedented double-digit territory in October and November last year, and to 8.4% for 2022 overall. The ECB has – with its tightening policy measures – mostly been leaning against the re-opening demand factors that first brought up inflation, while also guarding against a broadening of inflation after the second upward push by the energy supply shocks. As the latest figures show, headline inflation indeed appears to have peaked, and is gradually coming down, largely thanks to rapidly falling energy prices.

Relative to our current projections, the sharp decrease in energy prices could over time transmit to core inflation via lower prices for goods and services and bring headline inflation down faster. At the same time, the slowdown in growth seems to be even more shallow and short-lived than we had expected. Much of the latest economic data is surprising to the upside, with probably no recession in this 2022-23 winter – not even a technical one. This increased economic activity could, however, also improve the bargaining position of workers and contribute to more inflationary pressure down the road.

Underlying inflation dynamics

Clearly, lower headline and energy inflation is good news. A dark winter, at least in macro terms, likely has been avoided. But, inflation remains far too high. And measures of underlying inflation, that serve as an indicator of inflationary pressures in the policy-relevant medium term, still stand at high levels, and show few signs of abating yet. Along with the turn in headline, the focus of the Governing Council has also now shifted from energy and headline to breaking the underlying inflation dynamics.

Indeed, inflation has broadened over the course of last year. Costlier energy inputs and higher wage demands have translated in increasing underlying inflation, as for example measured by core inflation.

Today, core inflation – HICP excluding energy, food, alcohol and tobacco – stands at 5.2% and is expected to stay around this very high level for a few more months before levelling off. I would expect inflation in core goods to start falling first because price pressures from energy, supply chain disruptions and a weak euro are fading, but core services inflation could prove more persistent. [Figure HICP projections ECB] Going forward, the key question for me thus is how persistent core inflation will turn out to be.

When we look at the month-on-month dynamics of core inflation in the euro area, we see that our current situation is different than the one in the United States. Over there, core inflation is clearly on a decreasing path, which started sometime last summer. In the euro area, we do see the 3-months dynamics slowing down, but the 6 and 12 months dynamics are still increasing, which suggests that it will take some time before core inflation will slow down. [Figure core dynamics]

The largest upward risk to core inflation is a further increase in wage growth. While inflation expectations on the whole have remained quite well-anchored, labour unions have (understandably so) been pushing for higher wage growth to make up for the loss in purchasing power. So far, negotiated wage growth has remained quite modest with 2.9% y-o-y for the euro area (in November), but this number is projected to increase.

One would expect that the historically tight labour market gives employees a strong bargaining position for further wage increases. The staggered nature of wage contracting in the euro area leads both to an underestimation of current wage pressures as well as a likely more persistent wage drift. Forward-looking wage indicators confirm that wage growth will increase further in 2023. For example, in the Netherlands, the forward-looking wage indicator published by employer organisation AWVN shows 5.5% wage increase in January, based on newly-signed contracts only. But the longer core inflation stays high, the more plausible it becomes that employees will base their wage demand on past inflation and will attempt to get full compensation for their loss in purchasing power.

The ECB reaction function and communication

Not only the inflation problem has evolved; so has the ECB response. The phase of accelerated stimulus withdrawal is over: policy rates have – with hikes of historically large sizes – swiftly been brought into the range of natural rates, and balance sheet normalisation has been set in motion. However, a potentially persistent underlying inflation problem requires an equally perseverant monetary policy response.

Without a doubt, the direction of travel therefore remains up. The Governing Council will stay the course in raising rates at a steady pace and in keeping them at levels that are sufficiently restrictive for a timely return to our two percent medium-term target. This reduces inflation by dampening demand and guarding against the risk of an upward shift in expectations. Our decisions will continue to be data-dependent and follow a meeting-by-meeting approach.

I realise some observers have been confused by the combination of terms such as meeting-by-meeting on the one hand, and communication about our expected policy rate path on the other.

Let me try to explain how I see these elements interact with one another. The Governing Council started using the terms meeting-by-meeting and data-dependency to mark the turn from an era with persistent low rates and forward guidance about these rates, to a phase with a more uncertain inflation outlook and with policy that had to regain its flexibility. Ultimately, the Governing Council has always been guided by data and can – in principle – change policy at any given meeting, if we see this as necessary for the fulfilment of our mandate. The use of these terms just serves to emphasise these features of our process.

Now this does not imply that we would not have a certain baseline path in the back of our minds, especially for the near term. The Governing Council is convinced that, under a wide range of scenarios, rates need to go up further to restore price stability. That is why it is possible for us to communicate some assessment of the policy rate path that lies ahead of us; specifically the intention to hike by another 50 basis points in March.

This serves to reduce unnecessary policy uncertainty, which could induce undesirable financial market volatility. And it is consistent with our data-dependent and meeting-by-meeting approach in the sense that major and/or abrupt changes to the inflation outlook might always lead to a different policy decision at any upcoming meeting. The guidance that we extend is conditional and reflects an assessment based on contemporaneous information. It is a conditional baseline.

By extension, the rate path beyond March is more uncertain. At this point, as we still have quite some ground to cover, I consider it highly unlikely that the March hike will be our endpoint. And if underlying inflation pressures do not materially abate, maintaining the current pace of hikes into May could well remain warranted. At the same time, the farther policy rates are edging into restrictive territory and the stronger the cumulative impact of our tightening will be felt, the more important it becomes to fine-tune our actions. Once we see a clear and decisive turn in underlying inflation dynamics, I therefore expect us to move to smaller steps.

But absent such a turn, the ECB will continue to stay the course on its steady pace upwards, in pursuit of price stability for all euro area citizens.

Klaas Knot is the President of the Dutch National Bank.