by Francesco Domenico Attisano, Fabio Accardi & Roberto Rosato

The ESG (Environment, Social, Governance) issue is now on everyone’s lips. The buzzword of the moment is very often wrongly focused only on the environmental issue (see for example Climate Change). Instead, even examining the evolution of global risks, as shown by the latest Global Risk Report1, we note an ever-increasing worldwide perception of risks related to all environmental, social and corporate governance factors. Organisations should pursue sustainable development objectives that reward the creation of long-term value. For this purpose, as outlined in the new Italian Corporate Governance Code, “greater pervasiveness of corporate sustainability, integrated into its strategic perspectives” is essential.

All of this originates from the stakeholders’ expectations and mirrors specific needs of investors who, in the long term, aim to gain returns from investments in initiatives that have the ability to identify, manage and control global risks. If sustainable development is the guideline to follow in order to react to sudden scenarios’ changes even more impactful due to the pandemic outbreak, answers must be found in heterogeneous scopes, such as the individual, organisational, socio-political ones.

This is the learned lessons metabolised the most resilient organisations, which have been capable to resist negative events by anticipating their consequences and surviving successfully, even strengthened by the global emergency situation.

This capacity does not consist only of forecasting attitude, but pertains to structured processes that organisations must undertake, following systematic criteria and approaches.

How can ethics and compliance contribute to this process?

First of all, through an integrated approach that excludes the idea that compliance risks should be faced in isolation, without understanding their deep interconnections (first and foremost between administrative responsibility pursuant to Legislative Decree 231/01 and social responsibility pursuant to Legislative Decree 254/2016).

The approach must be synergic, both for the sharing of the areas of actions, in terms of risks and opportunities, and for the perception of the competitive advantages that may derive from it. In this sense, the diagram below shows how crimes risks “in the catalog”provided for in Legislative Decree 231/01 can be matched to the 3 ESG areas.

Figure 1: Offenses in Catalog 231 by prevalent ESG area, taken from Fabio Accardi Op. Cit.

Over the years, Policymakers are giving more and more weight to crimes related to ESG issues, and those provided for by Decree 231 are an example. This is consistent with the will to drive organisations to adopt effective prevention systems for those risk areas linked to particularly awful events occurred in the last twenty years2.

From a regulatory point of view, the provisions of Italian Legislative Decree 254 mentioned above regarding the Individual Non-Financial Statement (NFS) are exemplary. Indeed, Article 3 (c. 1.a) requires that the information contained in the NFS also regards “the business model for the management and organisation of the company’s activities, including the 231 Organisation Model (adopted pursuant to art. . 6, c. 1, let. A) of Italian Legislative Decree 231/01), also with reference to the management of the aforementioned issues. The link between the two regulations is therefore reaffirmed, as well as the interconnected purposes of the two provisions.

As for the second aspect, a different vision on compliance feeds the corporate risk culture and aims at competitive advantage. Even looking at international experiences, the purpose of “compliance programs” appears ultimately aimed at improving this culture. In this sense, the correct direction to follow is to avoid the so-called “paper programs”, that is, only formal programs that enunciate policies and procedure that are not actually applied, turning towards their effectiveness. In terms of sustainability, this kind of approach is critically highlighted with the term “green washing”, that is, giving a “green tint” to the communication, boasting attention to environmental and climate issues that is only apparent and devoid of substantial content.

Stakeholders’ expectations are believed to push towards virtuous evolution process, leading to lasting benefits over time.

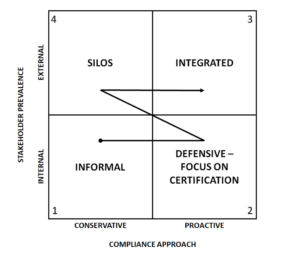

The matrix below summarises the latter concept, postulating evolutionary paths that lead organisations to deal with a plurality of stakeholders (external as well as internal).

Figure 2: Approaches to Compliance, source Fabio Accardi Op. Cit.

The matrix intersects the variable related to “prevalence of external / internal stakeholder interests” with that related to the kind of approach to compliance, schematically distinguishing between “conservative” vs “proactive” approaches. Proactive approach is intended to be aimed at identifying, assessing and mitigating compliance risks. On the other hand, a conservative approach is aimed at preserving the “status quo” by awaiting the consequences of events rather than anticipating them.

The matrix allows us to carry out some summary considerations based on four “maturity stages” of approach to compliance.

A) Informal

Taking “family and friends” companies as a reference, we can assume that the principles and values that guide the behaviour of organisations and individual belonging to this category are not necessarily codified in a formal document such as the code of ethics and also the internal procedural system. Shared principles and values drive behaviours and are the real cement of the organisation rather than formal policies and procedures.

B) Certificate – defensive

SMEs that compete on local or domestic market, adopting more articulated structures in term of organisation, need to comply with more complex regulatory systems and have to oversee the regulation of some typical functional areas, such as administration (accounting, tax and budget area), commercial (bid and tenders), production (technical specifications). The adoption of a code of ethics and management systems is a consequence, on one hand, to the need for more efficient work organisation, and, on the other one, to the ambition to obtain certifications, that are required for participating in some international or public tenders. A further reason that can lead to investing in compliance could be to obtain certificates that in the future may be useful in case of negative events (e.g. accidents at work) or disputes. The prevalence of internal stakeholders leads to the prevailing purpose of “safeguarding” or defense of the company’s owners and shareholders. Such organisations start to recognise the need to satisfy the expectations of external stakeholders, but they limit themselves to monitoring the compliance with mandatory regulations.

C) “Silos” approach

More advanced business and organisational models lead to a greater influence of external stakeholders than internal ones and further expand the panorama of applicable laws. The issues of administrative and social responsibility become important as they represent relevant concerns for external stakeholders, not just shareholders. Access to qualified lists (vendor lists) of suppliers of large clients requires demonstrating requirements that are not limited to legal certifications. In such cases, evidence must be given that a code of ethics and a Model 231 have been adopted and also effectively applied. It is similar for partnership agreements or loans, for which credit institutions usually require evidence that adequate policies and procedures on ethics and sustainability issues have been adopted. If organisations have not yet reached an adequate level of compliance risk culture, they tend not to anticipate the adoption of adequate safeguards but to adapt to regulatory changes or business needs. We define this kind of attitude a “silos” approach, meaning that each compliance issue is seen as a separate issue and not as part of an integrated plan. This can generate inefficiencies in the management of compliance processes, forcing organisation to review internal rules every time they decide to embark on one.

D) Integrates

More mature companies (usually multinational organisations that compete on international markets) must develop a culture of risk and compliance aimed at anticipating all possible events that may hinder the achievement of their objectives. Within these, compliance risks, and, those relating to corporate criminal and social responsibility of organisations, have great prominence because they constitute significant issues for all categories of stakeholders.

Conclusions

In conclusion, in designing compliance systems, consideration of stakeholders is crucial for the purposes of defining the strategic, operational, reporting and compliance objectives. For compliance issues we have focused on, having as a guide the creation of value only for shareholders or, instead, addressing the wide universe of stakeholders, determines the approach, within the two extremes outlined defensive – integrated).

An integrated approach, that considers the expectations of all stakeholders, is believed to guarantee adequate “assurance” in the pursuit of sustainable development goals, overcoming a notion of compliance as formal adherence to standards and rules. In this context, the ethics and compliance questions take specific relevance; otherwise, as described, any formal framework becomes a purely abstract construction and does not increase the resilience of organisations.

(1) Cfr. The World Economic Forum (WEF) (2022), Global Risk Report 2022

(2) See: the letter that Larry Fink, CEO of Blackrock (the world’s leading investment fund) sent to the CEOs of the companies in which the fund invests in which issues such as climate change and related social and economic issues. Fink L. (2021) “Letter to the CEO”

Francesco Domenico Attisano CIA, CRMA, CCA, QAR, is a Lead Auditor ISO 37001. He is also a Knowledge & Technical Manager at the Institute of Internal Auditors, Italian Chapter and Partner at operàri S.r.l. BCORP. He is a Strategic Consultant in Internal Audit, Risk & Performance Mgt, Anti-corruption & Compliance. He is also an author at the Italian website www.riskcompliance.it

Fabio Accardi is a Contract Professor of Business Auditing and CEIS Fellow at the Tor Vergata University in Rome. He is a faculty member of executive programs and courses at AIIA and Luiss Business School, and President of various Supervisory Bodies ex Dlg.s 231/01.

Roberto Rosato is an Internal Audit Manager at Webuild, CIA, CCSA, and has a Master of Science in Economics and Business. As of 2021, he is the Head of Internal Audit of Lane, the US Webuild strategic subsidiary. Previously, he worked as Astaldi’s Internal Audit Manager, focusing on operational audit, and as a consultant for PwC and Ernst & Young, business risk services. He is a member of the AIIA Publishing and Publications Committee, author of publications on Internal Control and Risk Management, and a AIIA teacher.