by Mark Dunn

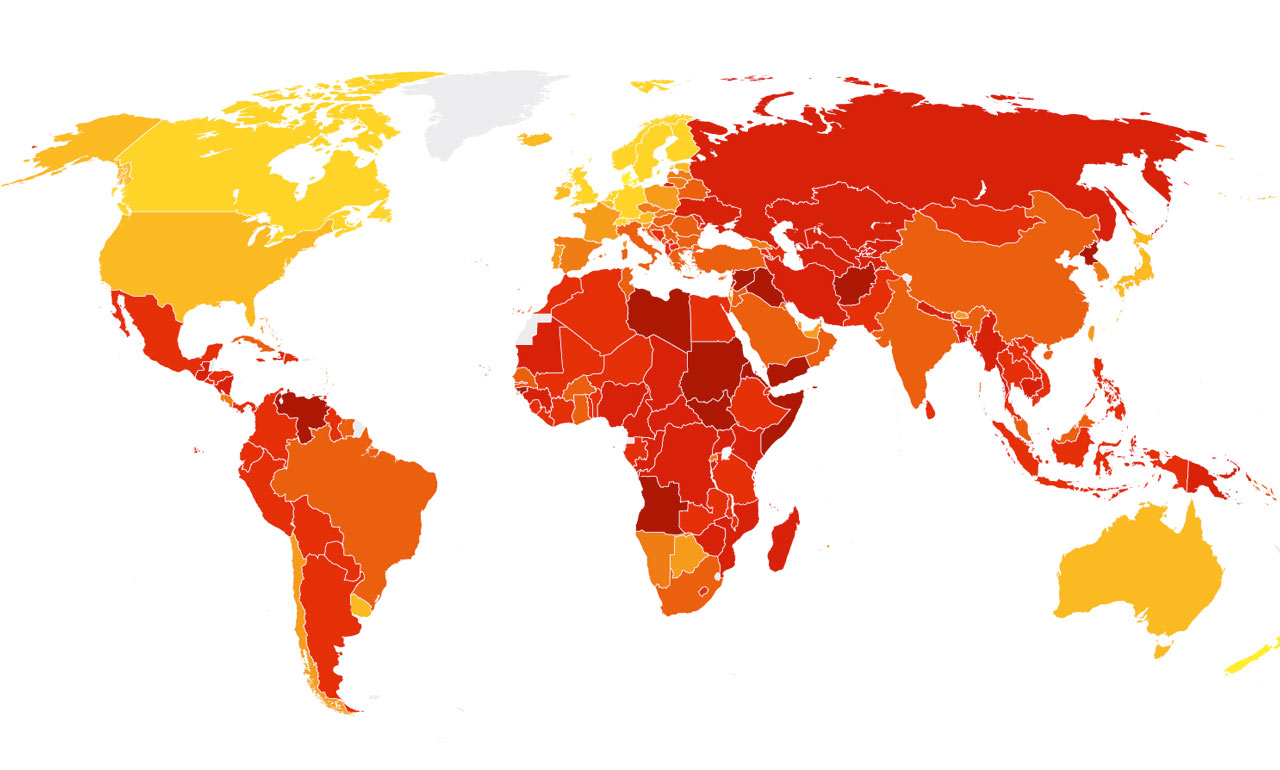

Transparency International has released its 2016 Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI). The CPI ranks 176 countries and territories on how corrupt their public sector is perceived to be. The index aggregates a number of different sources, including the views of business people and country experts.

Transparency International says the results show “the urgent need for committed action to thwart corruption”. The scoring system ranges from 0 (highly corrupt) to 100 (very clean) and, in the index, over two thirds of countries and territories scored below 50 with a global average of 43. More countries received worse scores than better scores compared to their performance in the previous CPI.

Global corruption increasing

The UK came tenth with 81, which is the same score it received last year. This is a strong improvement from five years ago, when it received a score of 74. The top performing countries were Denmark (90), New Zealand (90), Finland (89), Sweden (88) and Switzerland (86). Somalia (10), South Sudan (11), North Korea (12), Syria (13), Libya (14), Sudan (14) and Yemen (14) came bottom of the table.

The Netherlands was one of the five least corrupt countries in the last CPI with a score of 87, but this year it fell to eighth with 83. The top performing countries were Denmark (90), New Zealand (90), Finland (89), Sweden (88) and Switzerland (86). Somalia (10), South Sudan (11), North Korea (12), Syria (13), Libya (14), Sudan (14) and Yemen (14) came bottom of the table.

Corruption affects a country’s economy

In an analysis accompanying the 2016 results, Transparency International warns of the link between corruption and inequality. José Ugaz, Chair of Transparency International, says: ‘In too many countries, people are deprived of their most basic needs and go to bed hungry every night because of corruption, while the powerful and corrupt enjoy lavish lifestyles with impunity.’ This echoes the UN’s comments, on Anti-Corruption Day in December 2016, that corruption “can undermine social and economic development in all societies”.

The 2016 CPI is further evidence that there are economic benefits for a country if they make serious efforts to tackle bribery and corruption. The countries which perform best on the ranking tend to have the world’s strongest economies. Singapore is a good example of this. It is the only country or territory in Asia to make the top ten of this year’s CPI, coming seventh with a score of 84. A report last year by ethiXbase found that Singapore’s tough stance on corruption in the private and public sector has given the country “a significant competitive advantage over its neighbours”.

Index warns of corruption at all levels

Transparency International says the lower-ranked countries in their index tend to have “untrustworthy and badly functioning public institutions like the police and judiciary” and that even where anti-corruption laws are in place, they are often ignored. By contrast, higher-ranked countries tend to have stronger press freedom, access to information about public expenditure, stronger standards of integrity for public officials, and independent judicial systems. But the report notes that “the higher-ranked countries are not immune to closed-door deals, conflicts of interest, illicit finance, and patchy law enforcement that can distort public policy and exacerbate corruption at home and abroad”. Their message is clear: even in countries with the strongest records on corruption, there is no room for complacency in the fight against bribery and corruption.

A recognised tool for measuring corruption

The CPI is globally recognised as a useful tool for measuring corruption. It is used by many companies to understand the strategic risks of entering into a given market. When a firm is considering doing business in a country which scored poorly on the CPI, it should carry out a higher level of scrutiny as part of a risk-based due diligence approach.

The author Mark Dunn is Segment Leader for Entity Due Diligence Monitoring at LexisNexis.